The new Southampton General Hospital intensive care unit is squeezed in tightly between the curved Cardiac North Wing extension and a main entrance building

Building a new intensive care unit at Southampton General Hospital, BAM had to re-route explosive ‘quench pipes’, avoid interference with sensitive MRI imaging equipment, and even alter emergency helicopter flight paths. And then the coronavirus arrived. Stephen Cousins reports

BAM was just a couple of months into construction of a new intensive care unit for Southampton General Hospital when covid hit the UK and all hope of delivering a straightforward job evaporated.

The day after prime minister Boris Johnson delivered his infamous “Stay at home” speech at the end of March, the extension and refurbishment project lost around 80% of its workforce. “It was horrific, our supply chain just crumbled,” says Matt Crookes, project manager at the main contractor. “I spent the next week continuously on the phone trying to encourage people back, explaining the stringent new safety measures we had put in place.”

Workers soon returned – the project was classified as an ‘essential NHS project’ and letters were issued by the trust to subcontractors and supply chain – but the site’s proximity to the main hospital building and connection to the existing ICU, where NHS staff struggled with the dramatic influx of patients, have made the human cost of the virus apparent to everyone involved.

“The human side of things on site was really challenging: at the height of the pandemic when 1,000 people a day were dying in Britain, I had to use all my interpersonal skills to motivate people, reassure them and keep momentum going,” says Crookes.

The new General ICU (GICU) is located on the first floor of a five-storey block being built by BAM under a £21m ProCure 22 Framework project, the remaining floors will remain empty for the time being, subject to separate business case/cost plans.

View of the interior of the ICU

The job includes the fit out of the new GICU ready for occupation by staff and patients, at which point it will inherit the existing unit to carry out a full refurbishment. The new build element is due to handover at the end of September, followed by the refurb in March 2021.

Coronavirus aside, the project must contend with a complex array of technical challenges that threaten to derail a tight programme. Steel frame construction over a live MRI department had to avoid interference with sensitive imaging equipment, while close proximity to adjacent blocks required a rethink of the construction sequence and cladding.

It has been a logistical juggling act to manage the 12,000 people who walk past the project into the main hospital entrance every day, share site access with ambulances, and divert emergency aircraft landing on a helipad just a few metres away.

With no room for scaffolding, an alternative cladding design was developed

Clinical need

Southampton General Hospital is one of only two locations in the south of England to offer adults and children full onsite major trauma care provision, but the existing GICU accommodation had become extremely dated. When assessed against future activity projections and current design recommendations, the layout was inadequate in terms of capacity, bed bay sizes and functionality.

Jeff Belk, head of estates and capital projects at University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, told CM: “Visitors are frequently amazed that such positive clinical outcomes are achieved in this environment. With the added demands of the coronavirus pandemic, the importance of this new development was brought into sharp focus.”

Intensive care design has moved forward in recent years, with an increasing awareness of the impact that an internal environment can have on patients to improve wellbeing and promote faster recovery.

CGI of the unit exterior

Rehabilitation space

Architect Stride Treglown worked with the clinical team to understand patient needs and incorporate features such as abundant daylight, hoists to aid staff and encourage mobility and central rehabilitation space. A specially designed end-of-life room provides a therapeutic environment for patients and their relatives.

The arrival of the pandemic did not trigger a redesign, mainly because of the drive to bring new capacity and bed space on stream as soon as possible. Simon Boundy, divisional director and architect at Stride Treglown, says: “The GICU already incorporates a proportion of isolation and side rooms, which are key to the control of the current pandemic in the short and medium term.”

The project is of particular significance for BAM, whose legacy company Higgs & Hill built some of the original hospital buildings back in 1973. Crookes’ first job working as an assistant site manager was on the North Wing cardiac extension, completed in 2006 and located just 5m away from the new building.

“I’ve really come full circle, I know the hospital quite well, I know the people, how they operate and what they expect from a main contractor, which is a big advantage,” he says.

Construction projects are logistically complex places, but few have to contend with such a varied mix of human, vehicular and airborne traffic.

The site shares access with emergency blue light routes around the hospital, and a no-waiting zone means articulated lorries can only deliver at night by reversing into a special entrance.

The main hospital entrance has to remain open at all times, so a robust logistics and site compound plan was developed to create segregation between visitors and site activities. Highly qualified security staff manage the public 24-7 and watch out for local daredevils known to break into sites and climb tower cranes.

Emergency flights to a helipad next to the site would have come in directly over the project, so Crookes liaised with the Civil Aviation Authority and Southampton Airport to move flight paths to prevent potential collisions with the tower crane.

Higgs & Hill on the original hospital site in the 1970s

Gas and magnets

Existing hospital departments and functions remained operational, so the building had to be designed with careful consideration to the placement of structure, access for construction and fire escapes.

The new build is mostly reinforced concrete, but a lighter steel frame was erected, by contractor Stephens and Stuarts, over an existing single-storey block containing a live MRI suite.

The suite contains two cylindrical CT scanners fitted with super-conducting magnets that are sensitive to the presence of nearby metal. BAM had to coordinate closely with Siemens, the company that maintains CT equipment for the hospital, to ensure the steel frame would not distort image quality, either in its permanent state or when beams and columns were manoeuvred into position during installation.

If the CT scanners ever go down due to a fault, helium gas used to cool the magnets is rapidly expelled through quench pipes that project up from the roof. At an early stage of the project, the scanners had to be turned off (an extremely rare occurrence) and the pipes extended and diverted to make way for the new build, a process that required months of forward planning with the hospital.

The extension is located adjacent to two levels of operating theatres, which makes noise and vibration a source of concern where operatives had to break through into the existing building.

Below: Progress of the installation of the concrete floor slab

Patients first

Despite weekly coordination meetings and forward planning, some stoppages were necessary when urgent cardiac or paediatric surgery was taking place, says Belk: “This has been frustrating but everyone involved recognises the importance of the trust’s first value of ‘Patients first’.

To accelerate the programme and enable BAM to get in quickly to fit out on the first floor, a top-down method of construction was devised with columns and slabs for the upper floors erected in advance of the ground floor slab.

The block is squeezed in tightly between the curved (in plan) Cardiac North Wing extension and a main entrance building, with just 300-400mm clearance at the closest point. An intricate strategy for access, material deliveries and cladding installation was required to keep things flowing.

A wide lift shaft, able to accommodate lift cars big enough to hold patients in beds plus medical equipment and staff, was fitted with a goods hoist during construction to distribute materials onto the floorplates. This avoided the need to erect a hoist or scaffolding on the elevations and meant the facade could be left open for temporary access.

“Figuring out a way to clad the building when you’re that tight was difficult,” says Crookes. “On the elevation facing the main entrance building we didn’t have the working room for proper scaffolding so we developed an alternative cladding design, using composite panels instead of full rainscreen cladding.”

These were dropped in by tower crane and fixed into position from the floorplate.

Reality check

When covid entered the picture and normal site routines were thrown into disarray, BAM swiftly reformatted the work space to meet with social distancing guidelines and ordered non-frontline staff, such as design managers, planners and QSs to work from home.

“We picked ourselves up quickly and managed to get the supply chain back one by one,” says Crookes.

Remarkably, time lost during the first wave was clawed back and the project is currently reporting on budget and on programme. It is also encouraging that the number of infected patients in the existing ICU has come down into single figures.

“You talk to the clinical staff, and it’s just so motivating, there are such amazing resilient people here, we want to make sure we give them these new beds because it could be so important for the months ahead,” Crookes concludes.

BIM and asset data: the client challenged BAM to maximise its BIM output

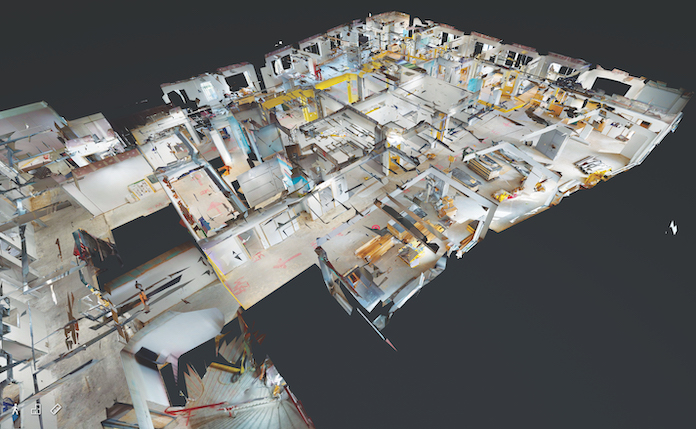

BAM used Matterport to roll out weekly virtual walkthroughs

BIM has become a priority for University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust as it strives to maintain a large and complex estate with multiple projects each year.

BAM Construct UK was challenged by the client to achieve a level of BIM output that was “probably more comprehensive than any of their recent projects”, says Jeff Belk, head of estates and capital projects at the trust.

The scope of asset data and asset labelling was designed to mesh BIM with the client’s computer aided facilities management systems and required significant fine-tuning.

When covid struck and non-essential visits to the project were suspended, the decision was made to roll out weekly virtual project walkthroughs showing works as they progress, created using the 3D scanning system Matterport.

The interactive panoramas cover every corner of the project and are navigated Google Street View-style using a mouse. “It has been great for illustrating the project to our stakeholders, charity fundraisers and other interested parties,” says Belk.

The system is now being exploited for more project-specific tasks, such as importing the 3D data into Revit to produce as-built drawings, which removes the need to physically send people onto site to take measurements. It will provide the trust’s maintenance team with a full photographic 3D record of service installations before they are covered by suspended ceilings.

“It has been a game changer for us and the client loves it,” says Matt Crookes, project manager at BAM Construct UK.

Project team

- Client: University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust

- Main contractor: BAM

- Architect: Stride Treglown

- Engineer: White Structures

- M&E design: Hulley & Kirkwood

- Client cost advisor: Faithful+Gould

- Specialist contractors:

- Mechanical: ARB Mechanical

- Electrical: Reavey Electrical

- RC frame: MJ Gallagher

- Steel frame: Stephens and Stuarts

- Drylining: AT Jones

- Lifts: Orona

- Groundworks: Goldmax